Evidence, and Evidence-Based Practices and Findings

Jim Grizzell,

MBA, MA, MCHES, ACSM-EP, FACHA

jimgrizzell@healthedpartners.org

Contents

Introduction........................................................................................................................................ 1

Importance

of Using “Evidence-Based Practice and Findings for CHES® and MCHES®.................................... 1

Types

of Evidence................................................................................................................................ 2

Anecdotal:

Not “Evidence-Informed” or “Evidence-Based”.................................................................. 2

Evidence-Informed......................................................................................................................... 3

Evidence-Based............................................................................................................................. 4

Steps

to Finding Evidence...................................................................................................................... 6

Reasons

Evidence-Based May Not be Used............................................................................................. 9

Summary............................................................................................................................................ 9

Thought

/ Critical Thinking Questions..................................................................................................... 9

Glossary

of Terms................................................................................................................................ 9

References

and Resources.................................................................................................................... 9

Introduction

The

Physical Activity Guidelines for

Americans has moved from evidence-informed in 2008 to evidence-based

in the 2nd edition published in November 20181. An emphasis in the continuing education

self-study course, The “Evidence-Based”

Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2nd edition) (2018)2, is to show how evidence

was gathered, the findings and resulting guidelines for 1) physical activity

and 2) health education/promotion to increase regular physical activity. This

paper gives an overview of evidence used for interventions to avoid harm and

improve health.

Importance of Using

Evidence-Based Practices and Findings for CHES®, MCHES® and CPH

Evidence-based is

emphasized because Certified Health Education Specialists (CHES®), the Master

Certified Health Education Specialists (MCHES®) Certified in Public Health (CPH)

and are expected to use evidence-based

practices. “Evidence” and “evidence-based” are stated In three of the seven

areas of responsibility of the Health Education

Specialist Practice Analysis (HESPA) 2015 Competencies3 for CHES® and

the MCHES®. And there are four sub-competencies (see

bullet point items below, two competencies are “Advance-1, for MCHES®) stating that CHES® and

the MCHES® should identify, apply and use evidence-based

findings. “Evidence” and “evidence-based” are stated six time in four of the 10

domain areas of the CPH Content Outline.4 NOTE: the term evidence-informed is not listed in the HESPA

Responsibilities and Competencies or CPH Content Outline.

Health Education Specialist Practice Analysis

(HESPA) 2015 Competencies

Area II: Plan Health Education/Promotion

·

2.3.3 Apply

principles of evidence-based practice

in selecting and/or designing strategies/interventions (Advance-1).

Area V: Administer and Manage Health

Education/Promotion

·

5.4.2 Identify evidence to justify programs

Area VII: Communicate, Promote, and Advocate

for Health, Health Education/Promotion and the Profession

·

7.3.5 Use evidence-based

findings in policy analysis

·

7.3.6

Develop policies to promote health using evidence-based

findings (Advance-1)

The

Responsibilities and Competencies for Health Education Specialists (web

page) have Areas of

Responsibility, Competencies and Sub-competencies for Health Education

Specialists 2015 (pdf,

note color coding for Advanced-1

and Advanced-2).

Certified

in Public Health Content Outline

Domain

Area: Evidence-based Approaches to Public Health

14. Apply evidence-based

theories, concepts, and models from a range of social and behavioral

disciplines in the development and evaluation of health programs, policies and

interventions

Domain

Area: Public Health Biology and Human Disease Risk

1. Apply evidence-based

biological concepts to inform public health laws, policies, and regulations

Domain

Area: Program Planning and Evaluation

10. Apply evidence-based

practices to program planning, implementation and evaluation

13. Plan evidence-based

interventions to meet established program goals and objectives

19. Use available evidence

to inform effective teamwork and team-based practices

Domain

Area: Policy in Public Health

5. Use scientific evidence,

best practices, stakeholder input, or public opinion data to inform policy and

program decision-making

Additionally, in 2001 Rimer, Glanz and

Rasband5 described why using evidence-based practices is important. They

wrote “Health educators and behavioral scientists should care about

evidence-based practice. Our goal is to improve the health of the public. Given

a shortage of resources, we must invest wisely in interventions that are most

likely to work. Moreover, we do not want to harm people by knowingly exposing

them to interventions that do not work, especially when there are proven

effective strategies. Using interventions that evidence shows are ineffective

not only wastes the resources invested in them but also crowds out alternative

actions. The best interventions are those with the greatest chance of changing

something that will make a desired difference.”

Types of Evidence

Anecdotal: Not “Evidence-Informed” or “Evidence-Based”

For

comparisons, it may be useful to see descriptions of health promotion practice

and findings that are not objective research evidence. Below are examples of how not evidence-based/informed might be described.

Key text to consider noting are in bold

and underlined.

From Richard Troiano, PhD (2008 PA

Guidelines Advisory Committee member) GWU Grand Rounds presentation in 2008.6

“. . .

public health practice . . , is moving towards a science-based, evidence-based

paradigm so that we don’t just kind

of do what we think is good, but we really have a strong evidentiary

base to support it.”

From US DHHS Office of Assistant

Secretary for Planning and Evaluation7

“In the

absence of evidence-based interventions, and often even when evidence-based

approaches exist, program operators frequently rely primarily on their personal experiences and good intentions

without careful consideration of related research evidence. While past

experience is valuable, ignoring existing evidence and developmental theory can

lead to missed opportunities, unintended results, and inefficient progress.”

From International Union for Health

Promotion and Education8

“The report concludes that programmes . . . are largely driven by “informed guesswork, expert hunches,

. . .”11

From

the journal Health Promotion Practice9

“Evidence-based practice is an

extension of evidence- based medicine, which moves

from “uninformed intuition, unsystematic clinical experience, and pathophysiologic rationale”

as the basis of clinical decision making, emphasizing instead the assessment of

clinical research evidence.”

From article in journal Health

Education and Behavior5

“Do we make decisions based on what

does or does not “work” according to the evidence or based on tradition,

intuition, precedent, and available resources? Would we replace what we feel

works best with what we know is better, based on evidence?”

Evidence-Informed

Below are examples of how evidence-informed has

been described. Key text to consider noting are in bold and underlined.

From Richard Troiano, PhD (2008 PA

Guidelines Advisory Committee member) GWU Grand Rounds presentation in 2008.6

“The other thing, if we just

look at those studies, those 560 studies on adiposity, you can see that

there’s quite a variety of study designs incorporated in that number. This

again reflects on why we had to

evolve to this evidence-informed concept

from an evidence-based concept. So out of the 560 studies, a little less than 200 were experimental

but that is both randomized and non-randomized studies.

So, if you took the drug trial

model and said I’m only going to rely upon randomized control trials, when

you’re looking at behaviors, you really don’t have much that you can go with.

So, you really need to cast a wider net and realize the tradeoffs when you’re

looking at observational and cross-sectional studies, but they do have

information to contribute.”

From National Alzheimer’s and Dementia

Resource Center (NADRC)10, 12

For consideration as evidence-informed,

an intervention must have

·

substantial research evidence that demonstrates

an ability to improve, maintain, or slow the decline in the health and

functional status of older people or family caregivers.

Evidence-informed interventions

(1)

have been tested by at least one quasi-experimental

design with a comparison group, with at least 50 participants; OR

(2)

have been adapted from evidence-based

interventions.

From article in journal British

Journal of Social Work11

“Evidence-informed practice (EIP) should be understood as excluding non-scientific prejudices and

superstitions, but also as leaving ample room for clinical experience

as well as the constructive and imaginative judgements of practitioners and

clients who are in constant interaction and dialogue with one another. . . . practitioners

will become knowledgeable of a wide range of sources—empirical studies, case

studies and clinical insights—and use them in creative ways throughout the

intervention process.”

Evidence-Based

Below are examples of how evidence-based has

been described. Key text to consider noting are in bold and underlined.

From article in journal Health

Education & Behavior5

. . . make decisions based on what does . . . “work” according to the evidence . .

. replace what we feel works best

with what we know is better, based on evidence?

“Jenicek called evidence-based public health “the process of systematically finding, appraising, and using

contemporaneous research findings as the basis for decisions in public health.”

From National Alzheimer’s and Dementia

Resource Center (NADRC) and Administration on Community Living (ACL) to receive

grants10, 12

For consideration as evidence-based, an

intervention must have

·

been tested

through randomized controlled trials and

(1)

be effective at improving, maintaining, or slowing the decline in

the health or functional status of older people or family caregivers;

(2)

be suitable for deployment through community-based human services

organizations and involve nonclinical workers or volunteers in the delivery of

the intervention;

(3)

have results published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal; and

(4) be translated

into practice and ready for distribution through community-based human services

organizations.

ACL Definition of

Evidence-Based Programs

·

Demonstrated through evaluation to be

effective for improving the health and well-being or reducing disease,

disability and/or injury among older adults; and

·

Proven effective with older adult population,

using Experimental or Quasi-Experimental Design;* and

·

Research results published in a peer-review

journal; and

·

Fully translated** in one or more community

site(s); and

·

Includes developed dissemination products that

are available to the public.

*Experimental

designs use random assignment and a control group. Quasi-experimental designs

do not use random assignment.

**For

purposes of the Title III-D definitions, being “fully translated in one or more

community sites” means that the evidence-based program in question has been

carried out at the community level (with fidelity to the published research) at

least once before. Sites should only consider programs that have been shown to

be effective within a real-world community setting.

Note: ACL

distinguishes between “evidence-based program” and “evidence-based

service/practice.” Services and practices are within programs. See answer to

question 8 of the Frequently Asked Questions on this page https://acl.gov/programs/health-wellness/disease-prevention. The “Resources”

section on this page also gives three items for “Understanding and Finding Evidence-Based

Programs.”

From Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2nd

edition)13

Use “. . . a

methodology informed by best practices for systematic reviews (SRs) developed

by the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Nutrition Evidence Library

(NEL),1 the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),2

the Cochrane Collaboration,3 and the Health and Medicine Division of

the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine SR standards to review, evaluate, and synthesize published,

peer-reviewed physical activity research. The literature review team’s

rigorous, protocol-driven methodology was designed to maximize transparency,

minimize bias, and ensure the SRs conducted by the Committee were relevant,

timely, and of high quality. Using this evidence-based

approach enabled compliance with the Data Quality Act,5 which states

that federal agencies must ensure the quality, objectivity, utility, and

integrity of the information used to form federal guidance.”6

Steps to Finding Evidence

The techniques of evidence-based medicine

involve these steps:14

(a)

asking research questions to precisely defining

the patient or population problem and the information required to solve it,

(b)

conducting an efficient literature search,

(c)

selecting high-quality relevant studies,

(d)

applying rules of evidence to determine their

validity,

(e)

describing the content of the study along with

its strengths and weaknesses, and

(f)

extracting the health message for application

to the problem.

The Physical Activity Guidelines for

American Advisory Committee followed each of the steps listed below. It was

instructed to examine the scientific literature. The Executive

Summary15 states that the Committee conducted detailed

searches of the scientific literature, evaluated and discussed at length the

quality of the evidence, and developed conclusions based on the evidence as a

whole. The Committee used state-of-the-art methods for systematic reviews to

address 38 research questions and 104 subquestions. Part E.

Systematic Review Literature Search Methodology16 details

the process used are described approaches to reviewing research. Part E lists

and describes the process as:

Step 1: Develop systematic Review Questions

Step 2: Develop Systematic Review Strategy

Step 3: Search, Screen, and Select Evidence to Review

Step 4: Abstract Data and Assess Quality and Risk of Bias

Step 5: Describe the Evidence

Step 6: Complete Evidence Portfolios and Draft Scientific Report

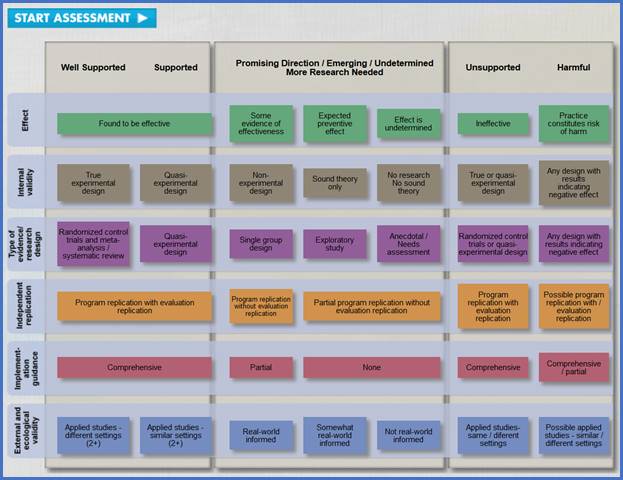

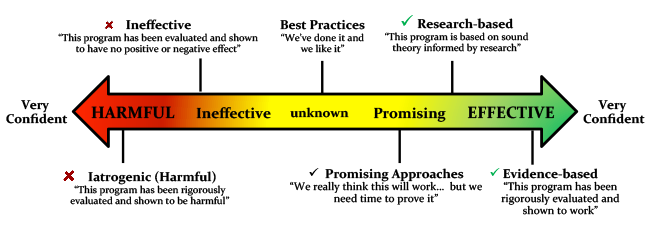

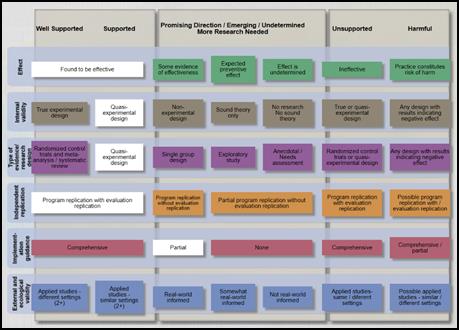

A set of steps to assess evidence is in CDC’s online tool, Continuum of Evidence of Effectiveness.16 The Continuum of Evidence of Effectiveness clarifies and defines standards of the Best Available Research Evidence. In Understanding Evidence, the Continuum is applied specifically to the field of violence prevention, but it can be used to inform evidence-based decision-making in a wide range of health-related areas. Evidence is assessed from harmful and unsupported through well supported. The dimensions covered include:

· Effect (effectiveness) – effective through practice constitutes risk of harm

· Internal validity – true experimental design through no research and research with results of negative effect

· Types of evidence/research (randomized control and meta-analysis / systematic review) through anecdotal / Needs assessment and design with negative effect

· Independent replication – program replication with evaluation through possible replication / evaluation

· Implementation guidance – comprehensive through none or partial

· External and ecological validity – two or more studies with different settings through not real world and possible same or different settings

Questions in the assessment include:

1.

Are there any indications from research or

practice that this strategy has been associated with harmful effects?

2.

Does the available research on this strategy

include two or more well-conducted studies (Randomized Control Trials or

Quasi-experimental designs)?

3.

Have any of these studies shown significant

effects in areas that you are concerned about?

4.

Is the study you are reviewing a Randomized

Control Trial?

5.

Does the study you are reviewing use a

Quasi-Experimental design?

6.

Has the program or strategy been implemented

in more than one setting?

7.

Has the program or strategy been evaluated in almost exactly the same

way in both of these settings?

8.

Are any of the following formal systems in

place to support implementation of the program or strategy?

9.

If formal systems to support implementation

are in place, are these resources available and accessible?

10.

Has the program or strategy been implemented

in two or more applied ("real world") settings?

11.

Does the strategy include components that are

consistent with an applied setting (i.e. uses materials and resources that

would be available/appropriate in an applied setting)?

12.

Has the strategy been implemented in ways that

mirror conditions of the “real world” (in other words, delivered in ways that

it would have to be delivered in real world settings)?

Click on the image of the ASSESSMENT tool on the next page to go to the web page with the assessment. The Iink is https://vetoviolence.cdc.gov/apps/evidence/continuumIntro.aspx#&panel1-8.

NOTE: the tool may work best with the Microsoft Edge browser. The tool uses Adobe Flash Player which may need to be installed on your computer if you find the highlighted boxes don’t appear after completing the assessment.

You can click through and answer the questions without having to login, use as a Guest. Once you complete the assessment several colored (green, brown, purple, etc.) should be white showing you where your answers mapped to each dimension. This will give you an indicator of the strength of evidence informing the various aspects of the strategy you are considering. Click on the white boxes to learn more about your results.

Reasons Evidence-Based May Not be Used

From

keynote presentation: “Evidence-Based Public Health” for 2018 Nevada Public

Health Association conference.17

·

Formal training - <50% of public health

workers

·

No single credential or license required – but

voluntary credentialing as Certified in Public Health, Certified Health

Education Specialist, Master Certified Health Education Specialist

·

Evidence-based practice needs multidisciplinary

approach and needs multiple perspectives

·

Interventions are based on: 1) political and

media pressure, 2) anecdotal evidence, 3) “the way it’s always been done

·

Barriers are: 1) lack of funds, skilled

personnel, incentives, time; 2) limited buy-in from leadership and elected

officials

From Pathways to

“Evidence-Informed” Policy and Practice: A Framework for Action7

“ . . . hindered by a lack of good-quality, synthesized evidence,

capacity to apply the evidence, and organizational support and resources to

make evidence-based decisions.”

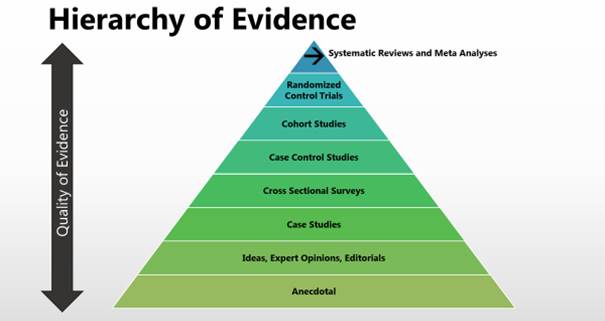

A Visual Description of Evidence: the Hierarchy

of Evidence18

The

hierarchy of evidence reflects the relative authority of the literature. Relative

authority can be depicted in a pyramid format where the base of the pyramid

includes research with the lowest quality of evidence (anecdotal) and the top

of the pyramid with the highest quality of evidence ( systematic review, meta-analyses

and random control trials). Quality of evidence refers to the range of bias and

opportunity for research to have systematic errors. For example, anecdotal or

opinions and editorials can have a significant level of bias based on the

author and their experience. On the other hand, randomized controlled trials or

systematic reviews control for bias through prescribed study designs and

represent the highest level of evidence.

Summary

Rimer, Glanz and Rasband4, and the

National Commission for Health Education Credentialing3 state that it is

important for health educators and health promotion professionals to use

evidence-based practices. There is a range of evidence to use for selecting

and/or designing strategies/interventions and policies. Likely least effective and

could harm and waste resources are interventions based on personal experiences,

tradition, intuition, doing what is thought to be good, and lack of resources.

Evidence-informed findings can provide support for interventions that could

improve, maintain or slow decline in health. Application of evidence-informed findings

may leave room for experience, and constructive and imaginative judgements. Interventions

and policies from the process of asking research questions, using a systematic

literature review strategy, assessing quality of data, describing the evidence

and applying the evidence is the basis of evidence-based practices.

Thought / Critical Thinking Questions

Think of a group, committee, organization or health

education/promotion team you might or do work with. Describe the group purpose,

members’ knowledge and experience, and your role (e.g., leader, topic expert,

member).

For the group, team organization you

described in the previous question and considering your role, how would you explain

anecdotal, evidence-informed and evidence-based? How do you or might you influence

the members t use evidence-based practices and

findings for interventions, strategies, programs and policies.? Explain how do

you or would you influence the members to use evidence-based practices and

findings for strategies, programs and policies?

Glossary of Terms*

Anecdotal - evidence in the form of stories that

people tell about what has happened to them.

Case-control study - A type

of epidemiologic study design in which participants are selected based on the

presence or absence of a specific outcome of interest, such as cancer or

diabetes. The participant's past physical activity practices are assessed, and

the association between past physical activity and presence of the outcome is

determined.

Cross-sectional study - A type

of epidemiologic study that compares and evaluates specific groups or

populations at a single point in time.

Intervention - Any

kind of planned activity or group of activities (including programs, policies,

and laws) designed to prevent disease or injury or promote health in a group of

people, about which a single summary conclusion can be drawn.

Observational study - A study

in which outcomes are measured but no attempt is made to change the outcome.

The two most commonly used designs for observational studies are case-control

studies and prospective cohort studies.

Prospective cohort study - A type

of epidemiologic study in which the practices of the enrolled subjects are determined,

and the subjects are followed (or observed) for the development of selected

outcomes. It differs from randomized controlled trials in that the exposure is

not assigned by the researchers.

Retrospective study - A study

in which the outcomes have occurred before the study data collection has begun.

Fidelity - Fidelity is the degree to which a program, practice, or

policy is conducted in the way that it was intended to be conducted. This is

particularly important during replication, where fidelity is the extent to

which a program, practice, or policy being conducted in a new setting mirrors

the way it was conducted in its original setting.

Meta-analysis - A review of a focused question that follows rigorous

methodological criteria and uses statistical techniques to combine data from

studies on that question.

Quasi-experimental - Experiments based on sound theory, and typically have comparison

groups (but no random assignment of participants to condition), and/or

multiple measurement points (e.g., pre-post measures, longitudinal design).

Random

Control Trial (RCT) –

From Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans: A type of

study design in which participants are randomly grouped on the basis of an

investigator-assigned exposure of interest, such as physical activity. For

example, among a group of eligible participants, investigators may randomly

assign them to exercise at three levels: no activity, moderate-intensity

activity, and vigorous-intensity activity. The participants are then followed

over time to assess the outcome of interest, such as change in abdominal fat.

From

Understanding Evidence: A trial in which participants are assigned to

control or experimental (receive strategy) groups at random, meaning that all

members of the sample must have an equal chance of being selected

for either the control or experimental groups (i.e..

Flipping a coin, where “heads” means participants are assigned to the control

group and “tails” means they are assigned to the experimental group). This way,

it can be assumed that the two groups are equivalent and there are no

systematic differences between them, which increases the likelihood that any

differences in outcomes are due to the program, practice, or policy and not

some other variable(s) that the groups differ on.

Systematic

Review -

From Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans: A review of a clearly defined question that uses systematic and

explicit methods to identify, select, and critically evaluate relevant

research, and to collect and analyze data from the studies includedin

the review.

From CDC’s

Understanding Evidence: The assembly, critical appraisal, and

synthesis of all relevant studies of a specific program, practice, or policy in

order to assess its overall effectiveness, feasibility, and “best practices” in

its implementation.

* Most definitions are from the Physical Activity

Guidelines for Americans (2nd edition) are available in the Scientific Report, Appendix H-1. Glossary of

Term [PDF – 874 KB] https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report/pdf/19_H_Appendix_1_Glossary_of_Terms.pdf.

CDC’s Understanding Evidence definitions

in its “Resources” web page https://vetoviolence.cdc.gov/apps/evidence/resourcesIntro.aspx#&panel1-7. Scroll down to the box “GLOSSARY.”

References and Resources

1. Office of Disease Prevention and Health

Promotion (2018). Physical activity guidelines for Americans (2nd

edition). https://health.gov/paguidelines/. Accessed on April 15, 2019.

2. Health Education Partners (2019). The evidence-based physical activity guidelines for Americans. www.healthedpartners.org/ceu/ebpag . Accessed on April 20, 2019.

3. National Commission for Health Education

Credentialing, Inc. (2015). Responsibilities and competencies for health education,

https://www.nchec.org/responsibilities-and-competencies. Areas

of Responsibility, Competencies and Sub-competencies for Health Education

Specialists 2015. Accessed on April 15, 2019.

4 National Board of Public Health Examiners

(2019). CPH content outline. https://www.nbphe.org/cph-content-outline. Accessed on May 8, 2019.

5 4. Rimer, B, DrPHKaren

Glanz. K, PhD, MPHGloria Rasband, G, BA, MA, (2001). Searching

for evidence about health education and

health behavior interventions.

Health Education

& Behavior: pp. 231-248. , First

Published Apr 1, 2001. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/109019810102800208

Accessed on April 18,

2015.

6 5. Troiano,

R. PhD. PA Guidelines (1st edition), Advisory Committee member

(2008). The 2008 physical activity guidelines

for Americans: development and dissemination of new federal evidence-informed recommendation.

George Washington University, December 9, 2008 GWU Grand Rounds

presentation

Original and Current links for the mp3 audio

and transcript

![]()

www.kaisernetwork.org/health_cast/hcast_index.cfm?display=detail&hc=3084

kaisernetwork.org/health_cast/uploaded_files/120908_gwu_troiana_transcript.pdf

- www.kaisernetwork.org no longer available –

Audio: www.healthedpartners.org/ceu/pag2nd/ei-eb/pag01_02_troiano_audio.mp3

Original Transcript: www.healthedpartners.org/ceu/pag2nd/ei-eb/pag01_02_troiano_transcript.pdf

PowerPoint: www.healthedpartners.org/ceu/pag2nd/ei-eb/pag01_02_troiano_powerpoint.pdf

Transcript with the audio’s times of

corresponding slides: www.healthedpartners.org/ceu/pag2nd/ei-eb/pag01_02_troiano_transcript_with

slide times.pdf

7. U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for

Planning and Evaluation, Office of Human Services Policy (2013). Best intentions

are not enough: techniques for using research and data to develop prevention programs.

https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/139251/rb_bestintention.pdf. Accessed

on April 16, 2019.

8. Bowen S, Zwi AB (2005)

Pathways to “evidence-informed” policy and practice: a framework for action.

PLoS Med 2(7): e166. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020166. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1140676/ Accessed on April 19, 2019.

9. Hill, E.K., MLS, AHIP, Alpi, K.M. MLS, MPH AHIP, Auerbach,

Marilyn, AMLS MPH, DrPH. (2010). Evidence-based practice

in health education and promotion: a review and introduction to resources,

Health Promotion Practice. May 2010 Vol. 11, No. 3, 358-366 DOI:

10.1177/1524839908328993 © 2010 Society for Public Health Education

10.

Administration on Aging. National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center. 2018 NADRC: grantee-implemented evidence-based

and evidence-informediInterventions. https://nadrc.acl.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/docs/EBEIIntervention2018final508revReadOnly.docx. https://nadrc.acl.gov/node/140. Access on April 16, 2019.

11. Nevo,

I., Slonim-Nevo, Vered. The myth of evidence-based practice: towards evidence-informed

practice. The

British Journal of Social Work, Volume 41, Issue 6, September 2011,

Pages 1176–1197, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq149.

Published: 24 January 2011. https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/article/41/6/1176/1720835.

Accessed on April 16, 2019.

12. Administration on Aging. Health promotion. https://acl.gov/programs/health-wellness/disease-prevention#future. Accessed on April 17, 2019

13. Office

of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Physical Activity Guidelines for

Americans (2nd edition (2018), Scientific report, part e. systematic

review literature search methodology. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report/pdf/06_E_Systematic_Review_Literature_Search_Methodology.pdf. Accessed

on April 15, 2019.

14. Olson, E. A. (1996).

Evidence-based practice: a new approach to teaching the integration of research

and practice in gerontology. Educational Gerontology, 22, 523-537.

15. Office

of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Physical Activity Guidelines for

Americans (2nd edition), Scientific report, part a. executive summary

(2015). https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report/pdf/02_A_Executive_Summary.pdf. Accessed on April 15, 2019.

16. Center

for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury Prevention & and Control:

Division of Violence Prevention. Understanding evidence: continuum of evidence

of effectiveness. https://vetoviolence.cdc.gov/apps/evidence/continuumIntro.aspx#&panel1-8. Accessed

on April 23, 2019.

17.

Grizzell, J. (2018). Nevada public health association, keynote presentation:

evidence-based public health. www.healthedpartners.org/cocreators/npha. Accessed

on April 17, 2019.

18.

National Library of Medicine. (2019). From problem to presentation:

evidence-based public health. https://nnlm.gov/classes/problem-prevention-evidence-based-public-health. Accessed

on May 2, 2019.

Additional

Resources

Toolkit on Evidence-Based Programming for Seniors (Community

Research Center for Senior Health)

A comprehensive guide on finding and implementing evidence-based

programs in a community setting.

http://www.evidencetoprograms.com/

National

Council on Aging Evidence-Based Program Resources

Guides to understanding, implementing, and building a business

case for evidence-based programs.

https://www.ncoa.org/center-for-healthy-aging/basics-of-evidence-based-programs/

Evidence-Based Leadership Council

This organization represents a small but notable group of

evidence-based programs that are shown to improve older adult health.

Evidence-Based Programs 101 (one-page

pdf)

http://www.eblcprograms.org/docs/pdfs/EBPs_101.pdf

The Evidence Continuum

https://www.nationalservice.gov/resources/evaluation/evidence-continuum

https://youtu.be/fzF08edFXmc

Experimental Design: Evidence-based Programs

http://www.episcenter.psu.edu/research/experimentaldesign

The Differences Between CHES® and CPH

https://www.nchec.org/cph-vs-ches